Ladder of Inference

We act on assumptions and beliefs built from filtered observations.

"If you want to understand how human systems function or fail, examine the logic that underlies their actions - not just the actions themselves."

In Agile teams, communication is never just about words. People react to much more than what is said, they respond to tone, timing, body language, and above all, their own interpretation of the situation. Behind every interaction lies a hidden structure of thought, which helps explain why two people can experience the same event and walk away with completely different conclusions.

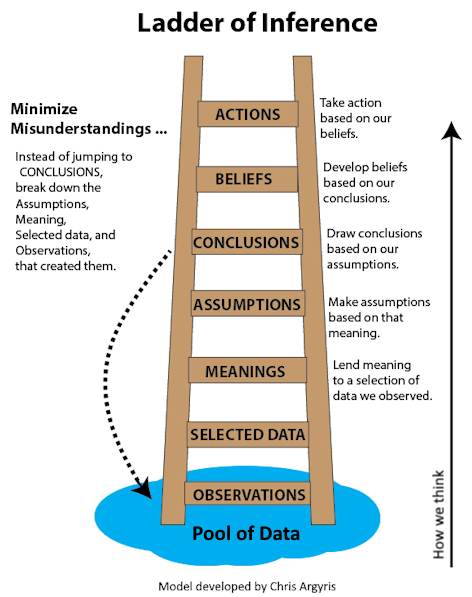

Developed by organizational psychologist Chris Argyris and popularized through the work of Peter Senge (The Fifth Discipline)1, the Ladder of Inference is a cognitive model that shows how humans move from direct observations to deeply held beliefs and actions. It maps the invisible steps we take, from noticing data, to interpreting meaning, to making assumptions, forming conclusions, and eventually taking action. What makes the ladder powerful, and potentially dangerous, is that we do all of this quickly and automatically, often without realizing we've done it.

For Agile teams that rely on rapid learning, continuous feedback, and shared understanding, these hidden leaps can be costly. When people respond to internal stories instead of observed facts, trust erodes, collaboration falters, and conflict festers. By becoming aware of how we climb the ladder, and learning how to walk back down it, Agile practitioners can create more open dialogue, better decisions, and healthier team dynamics.

At its core, the Ladder of Inference consists of seven rungs, each representing a mental step we take, often unconsciously, when interpreting and reacting to the world. To understand how these leaps shape our actions, it's helpful to walk down the ladder from the top:

- Actions:

- We act based on what we believe to be true. These actions, whether words, decisions, or silence, impact others and contribute to the system of interactions around us.

- Beliefs:

- Our actions are driven by beliefs, internal stories we've built about how things work, what people mean, or what outcomes are likely. These beliefs grow stronger over time, especially if left unexamined.

- Conclusions:

- Before those beliefs form, we draw conclusions about what is happening. We frame what we see and hear into a coherent narrative, often without checking whether it's the only possible interpretation.

- Assumptions:

- Those conclusions are built on assumptions, unstated expectations or inferences we make based on limited data. We assume intent, character, or meaning, filling in gaps with what "must" be true.

- Interpreted Meaning:

- To get to those assumptions, we first interpret the data we've noticed. This interpretation is deeply shaped by our cultural background, values, roles, and prior experiences.

- Selected Data:

- But we don't take in everything. Our attention filters the world, and we only notice certain pieces of information—those that feel familiar, confirm our expectations, or trigger emotional response.

- Observable Data and Experiences:

- At the base of the ladder lies the full reality: everything that is happening in a given moment. These are the raw facts, words spoken, gestures made, Jira tickets written, feedback delivered. This is the shared ground, even if few people stay rooted here.

This cycle happens quickly, silently, and repeatedly. In teams, it can result in conversations that appear logical on the surface but are deeply influenced by unshared mental models.

Impact on Agile Teams & Organizations

Agile thrives on transparency, empirical evidence, and shared ownership. The Ladder of Inference undermines these principles when team members act on private conclusions rather than shared understanding.

- Communication Breakdowns:

- Team members talk past each other, each operating from different mental models.

- Stakeholders misinterpret technical feedback as resistance or delay.

- Misaligned Goals:

- Teams make decisions based on inferred stakeholder intent rather than actual needs.

- Product Owners may prioritize features based on assumptions instead of validated learning.

- Unspoken Tensions:

- Disagreements remain unresolved due to fear of confrontation.

- Microaggressions or passive disengagement surface, reducing psychological safety.

- Ineffective Retrospectives:

- Reflection stays at the surface level, avoiding deeper root causes tied to beliefs or assumptions.

- Action items fail to address the systemic mental leaps that drive recurring issues.

Scenario

A UX Designer shares usability test results during a Sprint Review, suggesting a new navigation layout. A senior Developer, already under pressure from multiple bugs, replies, "Let's not keep redesigning everything. We need to stabilize".

Here's what happens on the ladder:

- The Designer observes the Developer's body language and tone.

- They select this data and interpret it as frustration.

- From past Retrospectives, they assume the Developer resents design feedback.

- They conclude that "engineering doesn't value user research".

- This reinforces a belief that it's "not worth pushing for better UX under this leadership"."

- They stop sharing usability feedback in future Sprints.

The Developer, meanwhile, had simply hoped to reduce scope for the current release. No harm was intended. But both are now climbing parallel ladders, resulting in disengagement and missed opportunities for improvement.

Ways to Mitigate

Agile coaches, leaders, and team members can reduce the negative impact of inference by making thinking visible and encouraging inquiry.

- Teach the Ladder Explicitly:

- Introduce the model during workshops or Retrospectives.

- Share personal examples of ladder climbing.

- Model Curiosity Over Certainty:

- Ask "What did you see that made you think that?"

- Encourage "Could there be another interpretation?"

- Use Reflective Structures:

- Practice rounds where team members first share observations before offering interpretations.

- Apply techniques like "Name it to tame it""" to reduce emotional reactivity.

- Create Safe Feedback Channels:

- Use anonymous feedback tools when trust is low.

- Facilitate one-on-one ladder reflection after tense moments.

- Revisit Shared Mental Models:

- Align on definitions, goals, and norms regularly.

- Make working agreements explicit and revisitable.

Conclusion:

Agile environments are fast-moving and relationally intense. The Ladder of Inference reminds us that what we believe is happening often differs from what is happening. Left unchecked, these differences shape decisions and relationships in ways that compromise agility. But with awareness, dialogue, and curiosity, teams can descend the ladder together, moving toward understanding rather than assumption.

Key Takeaways

- The Ladder of Inference shows how people unconsciously move from facts to action through interpretation, assumption, and belief.

- Agile teams often climb the ladder too quickly, leading to miscommunication, tension, and stalled improvement.

- Teaching the model and building reflective practices into team culture can improve alignment and trust.

- Scenarios involving design, feedback, or stakeholder interpretation are especially prone to inference traps.

- Slowing down and checking reasoning prevents premature conclusions and reactive decisions.

Summary

Argyris's Ladder of Inference is not just a theoretical model, it is a practical lens for seeing where Agile conversations go wrong. In the compressed pace of modern teams, unspoken assumptions can ripple outward and shape culture. By stepping back and examining how we think, not just what we think, Agile teams can strengthen their feedback loops, improve psychological safety, and make better decisions rooted in shared reality.